Here’s a story: a young woman is kidnapped by a sailor and forced to sail away with him and a crew. The sailor ‘loves’ the woman, but she never asked to be dragged onto the boat. A storm blows up, kills the sailor and crew, and drives the boat northward. The woman finds herself alone at the North Pole, thousands of miles from family, with no crew to help her get home. But then a mysterious portal opens in front of her. Rather than face a cold and lonely death, the woman walks through, and finds herself in a strange new world where all the creatures speak, where there is only one language, pure monotheism, and absolute peace. The creatures welcome the woman as their Empress, and they all work together to make scientific discoveries.

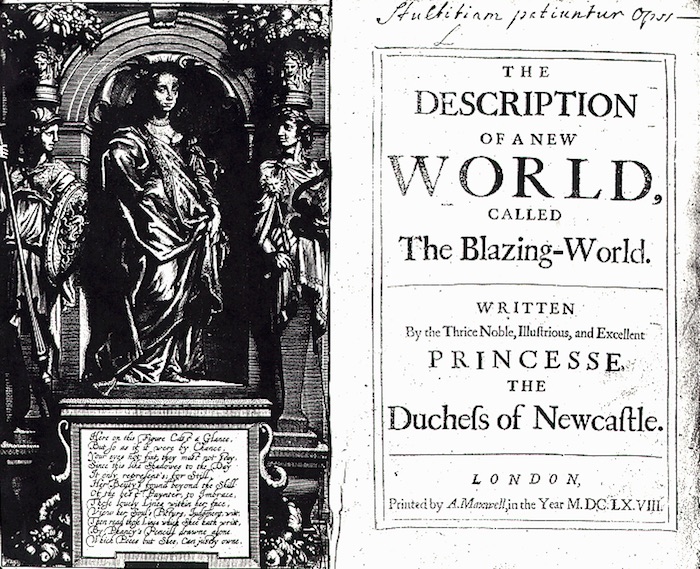

This is the basic plot of “The Description of a New World, Called the Blazing World”, which was written by Duchess Margaret Cavendish, and published in 1666. As the intrepid archivists of Atlas Obscura have pointed out, it may be our earliest example of science fiction and it was written by a shy, lonely woman who, despite being mocked for having career aspirations, married fantasy, proto-sci-fi, and philosophical thinking 150 years before Mary Shelley’s classic Frankenstein.

Margaret Cavendish was born in 1623 to a family of relative means. She became a Maid of Honor to Queen Henrietta Maria, whom she followed to France in exile during the English Civil War. When she returned to England, she was a Duchess with a loving, supportive husband, and between his influence and her own charm and intelligence she was able to observe experiments at the British Royal Society, write, and, increasingly, seek fame through outrageous social behavior. If she’d been born a man, she would have been a poet, and probably a dandy, snapping off witticisms right along with Alexander Pope. Instead she went through painful ‘treatments’ that were meant to help her bear children, and she was mocked as “Mad Madge” by other nobles.

Now obviously there are other contenders for “earliest sci-fi author”, and you could argue that this story is more in line fantasy/philosophical exercise typical of the time—Cavendish does write herself into the book as the Duchess, a friend of the Empress. The two women are able to disembody themselves, and as (gender-free!) souls they travel between the worlds, occasionally possessing Cavendish’s husband to give him advice, particularly on sociopolitical matters.

But, the reason I accept Cavendish as a science fiction author is that her story is fueled by her study of natural philosophy. She (like Mary Shelley, later) attempted to take what was known about the world at the time, and apply a few of the ‘what-ifs’ of scientific experimentation to it, rather than just handwaving and saying “God probably did it.” The Empress employs the scientific method in her new world, investigating the ways in which it differs from her own. Cavendish also writes of advanced technology, as Atlas Obscura observes:

[She] describes a fictional, air-powered engine that moves golden, otherworldly ships, which she says “would draw in a great quantity of Air, and shoot forth Wind with a great force.” She describes the mechanics of this steampunk dream world in precise technical detail. All at once, in Cavendish’s world, the fleet of ships links together and forms a golden honeycomb on the sea to withstand a storm so that “no Wind nor Waves were able to separate them.”

Unlike Mary Shelley, Cavendish published her book under her own name, and it was actually included as a companion piece to a scientific paper, Observations upon Experimental Philosophy, where it was probably supposed to provide a fun story to help lighten the dry academic work it was paired with. You can read more about Cavendish and her work over at Atlas Obscura. And if that isn’t enough feminist proto-sci-fi for you, Danielle Dutton has written a novel based in Cavendish’s life, Margaret the First, which was released earlier this year, and you can read the full text of The Blazing World here!